Craft your unique photographic style with intent.

We have all heard it at some time or another – the belief that that more megapixels translate to higher image quality is one virtually every photographer or smartphone shooter will be familiar with. It was this assumption that paved the way for the colloquial ‘megapixel race’ back in the early 2000s, where camera companies like Nikon and Canon often touted the number of pixels as a marketing tool to sell new models.

Today, it is widely accepted that the megapixel race concluded sometime around 2010. From then on, camera companies vowed to shift their focal points to improving other aspects of image quality, low-light performance, and new features. Around this time, camera companies had begun to accept that cramming as many pixels onto a sensor as possible would often create more problems than it would solve, giving rise to issues like noise and poor low-light performance.

Effectively, they realised that around twelve megapixels was more than sufficient for most shooters, and that there were bigger improvements to be made in the ISO and dynamic range department.

In light of this, it was Canon who made the pivotal move to introduce a compact camera with a lower megapixel count. In 2009, they released the PowerShot G11, a high-end compact digital camera equipped with a 10-megapixel sensor, a 5x optical zoom lens, RAW shooting capabilities, an optical viewfinder, and a variable-angle LCD screen.

With so many fancy features, it was easy to get swept up in its allure, but there was one area that stood out in particular. Canon’s decision to lower the resolution of the sensor to 10-megapixels, down from 14.7 in the previous PowerShot G10, was a bold move, particularly at a time where companies where desperately fighting to outperform one another in the resolution department.

Initially, many consumers felt that this was an odd decision on paper, before realising it was Canon’s way of preventing the placement of too many pixels onto a small sensor, which had previously caused problems. The G10 in question suffered due to its high pixel density on a smaller sensor, resulting in grainy, noisy images, especially above ISO 400.

By reducing the megapixel count, Canon was able to increase the size of individual pixels, allowing each one to gather more light, and thereby enhance the camera’s versatility and overall image quality, preserving more details in darker areas. It wasn’t rocket-science by any means, but incredibly innovative for the time.

By the end of the process, a new discovery had been formed – the number of megapixels in a sensor is just one in a number of aspects that define how well a camera actually performs. Fast forward fifteen years, and Canon have remained true to this belief and stuck by the notion that megapixels don’t solely equate to strong imagery.

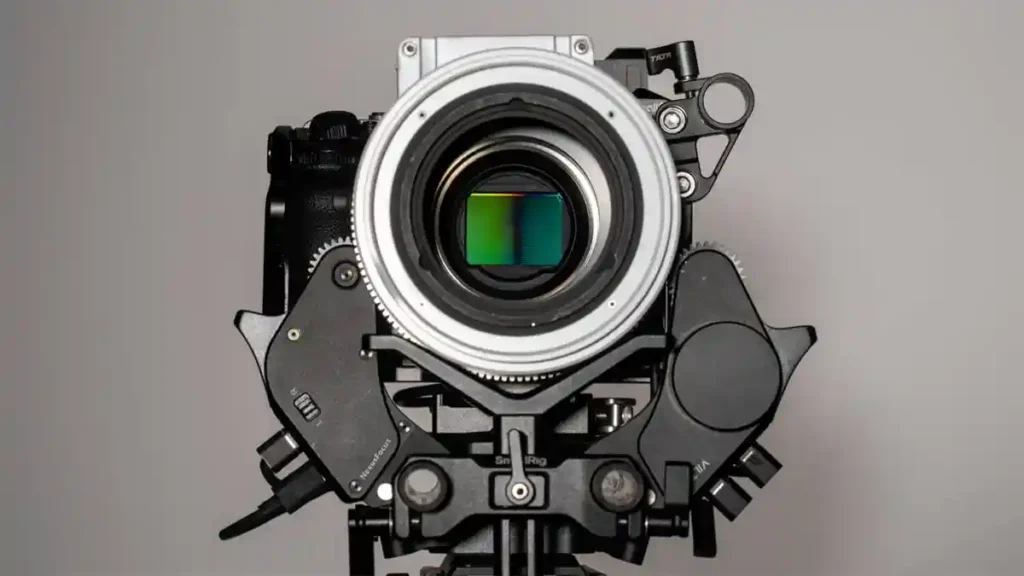

The EOS R6 Mark III for example, has a 32.5MP full-frame sensor, proving that Canon have recognised the need for modern workflows to share a balance of resolution, speed, and hybrid functionality, rather than just having a whopping number of pixels.

But why is 32.5 megapixels such a good choice overall? Well, there are many factors at play here, but the most obvious is that at this resolution, images can still be captured in lossless detail without overkill file sizes which can slow down the editing process as well as consume more battery on the camera.

Let’s not forget that many of those extra pixels are often wasted when they are viewed on a small screen like a phone or laptop. A 32.5MP image captures enough detail for high-quality A2 prints and significant cropping. This flexibility means fewer lens changes in the field and more creative freedom when composing the final image.

Beyond the sensor itself, several features of the Mark III leverage its resolution for more efficiency. For example, it can shoot full-resolution stills at up to 40 frames per second with the electronic shutter, thanks to the sensor’s fast readout and the dual card slots that support the high write speeds required.

It’s also interesting to compare Canon’s offering with Nikon’s rival, the Z6 III. But how do the R6 III and the Z6 III differ, and which one is going to be better suited to your needs? Well, given how similar the two are, it’s mostly a matter of preference. However, Canon’s camera starts at a whopping £2,799.00 while Nikon’s Z6 feels much more attainable at £1,539.99.

In terms of specifications, the main differences are that the Z6 has a partially-stacked 24.5MP sensor, a higher-resolution EVF, and faster burst shooting, while Canon’s R6 has a higher-resolution 32.5MP sensor that offers more cropping flexibility and a slightly better-known autofocus system that will be very beneficial for certain scenarios like wildlife shooting.

The R6 III also has the advantage of an open gate video mode which utilises the full width and height of the camera sensor, allowing for great cropping flexibility, while the Z6 has the more traditional 120p 4K video option.

If stills and video cropping flexibility is important to you, then Canon takes the win. But if price is a concern, and you want a more versatile camera that is a fantastic all-rounder, then the Nikon Z6 is perhaps the more appropriate choice.

Still, the Mark III’s full-frame sensor, combined with the powerful DIGIC X processor, maintains brilliant low-light performance with an expandable ISO range up to 102,400, which is a key advantage over many similar-priced cameras.

And keep in mind that to truly make the most of Canon’s higher resolution and cropping potential, you will need to pair it with high-quality lenses, such as the RF 100-500mm or RF 600mm, as these are strong choices for achieving longer focal lengths which is very important for wildlife and sport photography.

In conclusion, the Canon EOS R6 Mark III remains a strategic choice, providing the quality and flexibility needed for diverse professional applications while optimizing the speed and efficiency of the overall workflow. It strikes a perfect balance for hybrid shooters who need high-quality stills and professional-grade video in one versatile and more affordable body than the R5 II.